UCI Brain Camp taps into the teenage brain

Middle and high school students share experiences in the neurosciences

For two weeks this summer, the halls and laboratories of the UCI Center for the Neurobiology of Learning and Memory buzzed with the energy of curiosity, creativity and community – the energy of Brain Camp.

“Like regular summer camp, only better” is how Manuella Oliveira Yassa, a former middle school teacher and UCI Brain Camp founding director, describes the program. “Brain Camp is Disneyland for young brain enthusiasts.”

Founded in 2019 as one of the only summer neuroscience camps in the country, UCI Brain Camp aims to immerse teens in the wonders of the brain and equip them with the skills necessary for success in science research. This year, the day camp hosted more than 40 middle and high school students.

While the program is non-residential and most campers are Orange County residents, a handful of teens from Northern California, Maryland and Florida convinced their parents to turn Brain Camp into a family California vacation. When asked how Brain Camp can be made better, the most common responses from students are “extend it to 4 weeks” and “make it residential, so we don’t have to leave.”

What happens at Brain Camp that makes it so special? Brain Camp taps into the adolescent brain’s natural drive to experiment. We all know that adolescent brains go through a unique transition. Holding on to the curiosity of childhood while stretching toward the independence of adulthood, adolescent brains don’t respond well to “because that’s how it is” and would rather learn for themselves, usually by taking risks and making mistakes. This, combined with the adolescent brain’s growing capacity for complex and critical thinking makes the adolescent the ideal scientist.

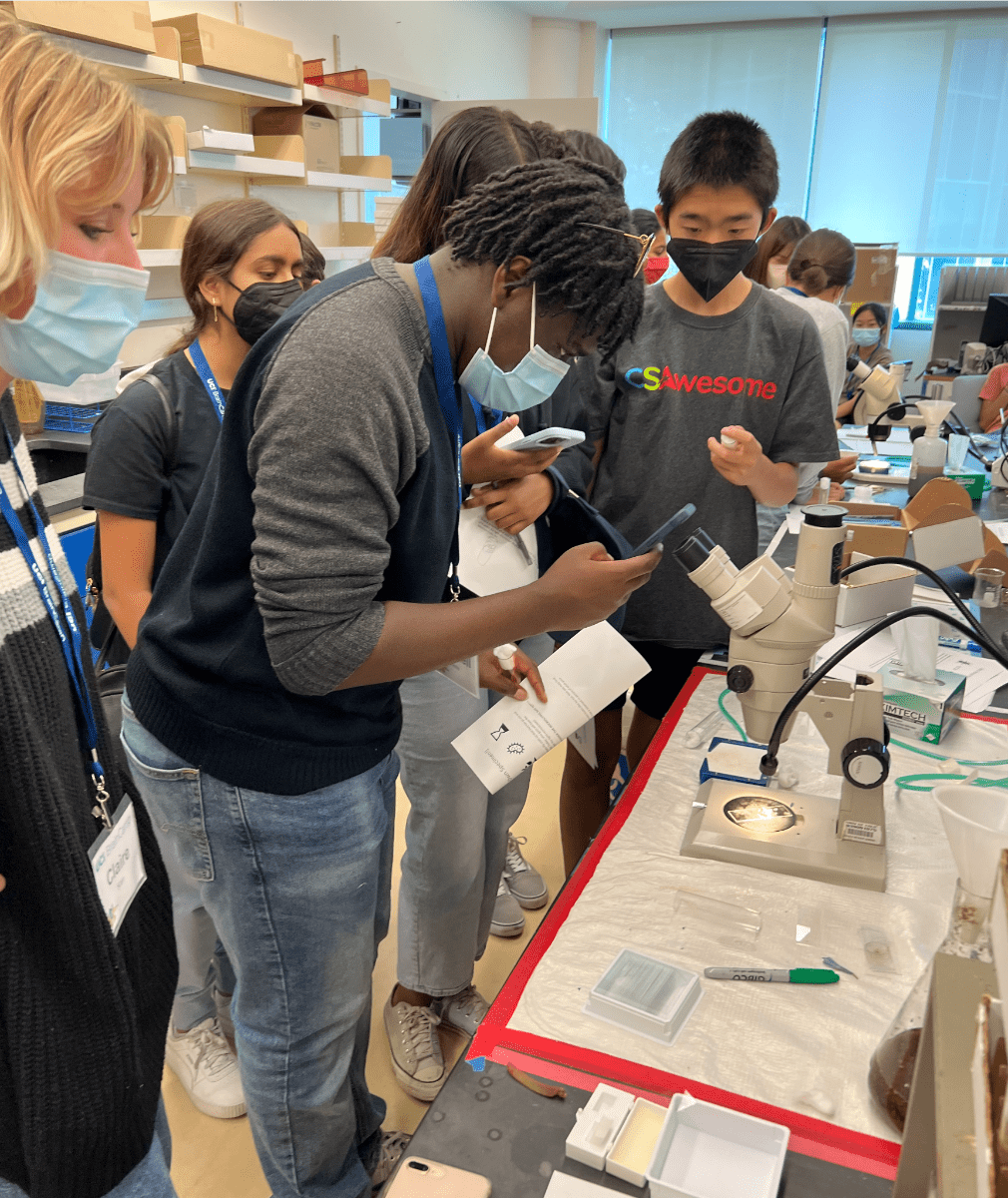

In Brain Camp, teens get to do what they do best – learn by doing. They engage in out-of-the-box thinking and are encouraged to ask questions and take risks, all while working in teams with peers and making new friends.

The questions tackled in Brain Camp center around the nervous system, the scientific process and the path to a neuroscience career: How is the brain organized? How does it develop? How do we use our senses to interact with the world around us? How do we research the human brain? How do we use animal models in neuroscience research? What happens when the brain is injured? What kinds of cells make up the brain? How do those cells communicate with each other? How do we design experiments to explore the brain? How do we make sense of the data from research studies? What is the scientific peer-review process? How does one become a scientist?

The answers emerge from activities that bring neuroscience to life – hands-on experiments and demonstrations, exploration of real university laboratories and discussions with real scientists. This year’s Brain Camp counselors included eight Ph.D. students who served as science mentors and worked closely with campers every day. Students built relationships with their mentors, engaging in conversations not only about research but about the mentor’s path to science.

Among the highlights of this year’s Brain Camp was learning alongside world-renowned neuroscientists, like UCI’s Georg Striedter, who joined us one week before the release of his new book, Model Systems in Biology: History, Philosophy, and Practical Concerns. In addition to authoring several books including one a leading neuroscience textbook Neurobiology: A Functional Approach, Striedter introduced campers to a popular topic in biomedical research – translation from animal models – and led them on a journey of critical exploration where they evaluated the opportunities and challenges of this approach and contemplated what the future of neuroscience holds.

After spending the first week learning the fundamentals of neuroscience and exploring cutting-edge research tools, students were ready to design and conduct their own research studies. Working collaboratively in groups, campers bonded over their love of neuroscience while collecting data, often immersing themselves in deep and meaningful conversations about the brain and research methods. Research study topics ranged from investigating whether learning styles affect learning outcomes to exploring the effects of temperature on the velocity of neuronal communication (action potentials) in the earthworm. Campers presented the results of their research projects during the last day of camp during the Brain Camp Showcase, which was attended by parents and family members and even some of the campers’ science teachers.

As intense as Brain Camp is, it’s still a summer camp at the end of the day. Between the brain dissections and thoughtful discussions, students tie-dyed camp shirts, enjoyed lunch in the courtyard, played volleyball in Aldrich Park, took trips across the street to University Town Center, visited the UCI bookstore and received their very own got brain? branded mugs as a souvenir.

If you want to learn more about supporting this or other activities at UCI, please visit the Brilliant Future website at https://brilliantfuture.uci.edu. Publicly launched on Oct. 4, 2019, the Brilliant Future campaign aims to raise awareness and support for UCI. By engaging 75,000 alumni and garnering $2 billion in philanthropic investment, UCI seeks to reach new heights of excellence in student success, health and wellness, research and more. The Center for the Neurobiology of Learning and Memory plays a vital role in the success of the campaign. Learn more by visiting https://brilliantfuture.uci.edu/center-for-the-neurobiology-of-learning-and-memory-2