“17 April 2001?” I ask Krystyna Glowacki, 24, over Zoom.

“That was a Tuesday,” she shoots back after less than half a beat. It was.

Hottest temperature ever recorded in Oman?

I’ve barely finished the question before she verbalises her confident response: 50.8C. Correct. Every hair on my arm stands up.

And Mongolia? I’m throwing in far-flung places to really test this seemingly superhuman brain. 44C, right again.

Coldest in Germany? “Minus 45.9 degrees, in a sinkhole in Bavaria on December 24, 2001.” I sit there blinking. At this point I actually laugh. Her memory is so good, it’s preposterous.

Glowacki, from the New South Wales central coast, can name the hottest and coldest temperature recorded in every country in the world, along with the location and date that record was set. She can also name the longitude and latitude of every major city in the world. Despite lockdown, she transports me across oceans, accurately naming coordinates from San Francisco to Berlin in quickfire responses.

‘I read it once and retain it’

“I just have the ability to retain information. It’s just there,” Glowacki says. She only needs to scan the internet once or twice to take and keep anything in.

Glowacki is on the autism spectrum and has superlative memory and calendar recall skills.

Genuinely “photographic” memories are exceptionally rare. Also called highly superior autobiographical memory (Hsam), this ability is only verified by one institution, the Centre for the Neurobiology of Learning and Memory at the University of California, Irvine.

The centre describes people with Hsam as having “a superior ability to recall specific details of autobiographical events”. They “tend to spend a large amount of time thinking about their past and have a detailed understanding of the calendar and its patterns”.

To date, the centre’s laboratory has identified fewer than 100 occurrences of Hsam worldwide.

Although she has not undergone the rigorous testing required to be classified as having Hsam, Glowacki does exhibit some of the same traits.

So far, just one person identified as having Hsam is Australian: Rebecca Sharrock.

While Sharrock’s gift has attracted much media attention, less has been written about the cohort just below the Hsams: those with superlative memories, probably the best within their social or professional circle.

In neuroscience terms, they’re deemed as having “highly average to superior” memories; not genuinely photographic, but nonetheless astonishing.

‘I can remember every minute a goal was scored’

One such person is Dave Huggan, 46, nicknamed “Statto” for his incredible recall abilities.

He looks to the left as I ask him, over Zoom, the finalists in the 1903 FA Cup final. “Bury 6, Derby Country 0,” he says, before relaying the minute all six goals were scored by five different scorers, whom he names. We do this for several different years: he remembers every FA Cup finalist, scorer and minute scored since 1872, and when tested, he’s accurate about 95% of the time.

Like Glowacki, Huggan did not have to train for his feats of memory; however, he is not autistic.

“I can see the goal now, Gary,” he says of a later FA cup final, he accurately recounts. “I can see it go in from the far side of the field into the corner of the net.”

His eyes light up but mine glaze over. “I know it’s boring; that’s why I perform,” Huggan, from Sydney, says. “Otherwise it’s just facts. It’s hard to get people to engage. You need that entertainment factor.”

He then, almost alarmingly, rattles off every Melbourne Cup winner, in chronological order, in the frenetic style of a horse race commentator. Later, he sends me a video of him singing a megamix of every UK Christmas No 1 song.

“I began absorbing football facts aged 17 and people started noticing,” he says. “I just remember all of it from reading it once or twice.”

People still notice. He performs the No 1s medley annually at his office Christmas party; same for horse winners on Melbourne Cup day.

Unfortunately, it didn’t translate into academic exam success in his weaker subjects like maths and science: “I only remember things I like.”

‘The magic ingredient is paying attention’

For those born without the natural gift of phenomenal recall, there are tricks and techniques that train the brain into a better memory muscle.

According to Gail Robinson, professor of clinical neuropsychology at the Queensland Brain Institute, “the magic ingredient is paying attention”.

“In neuropsychology, if someone has a patchy memory, we look at how good their attention is; what else are they thinking about,” she says.

“Paying attention is a different skill from memory. And it’s absolutely a skill you can develop. That part is nurture. It requires focus, being selective on the information you retain, and encoding that. Deep focus is key – and social media feeds are killing that skill.”

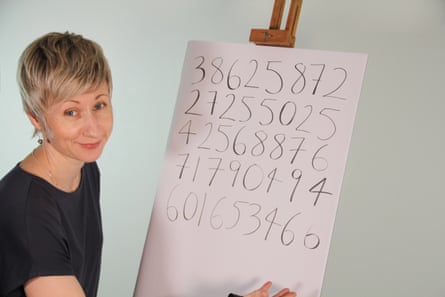

Anastasia Woolmer, 44, is living proof that memory can be improved. A two-time Australian Memory Champion and the first female to win this title in Australia, she achieved this goal after only five months of self-training.

“It was astounding to me,” she says. “You go your whole life thinking what you’re born with is it. I’d forget names at small dinner parties. I think impostor syndrome is common. It felt liberating: if I set my mind to something, I can learn it really quickly and gain confidence.”

Woolmer was inspired by Moonwalking with Einstein by Joshua Foer, which suggests brain training, rather than naturally gifted people, account for most USA Memory Championship finalists.

The memory techniques, known as mnemonics, use imagery to aid encoding and retrieval. Another, the memory palace, dates back to the fifth century BC and “places” abstract things on to actual objects, narrativising memory.

In Woolmer’s case, she used her dance background to remember the first 1,000 digits of pi. “I attached a movement for every number sequence from 000 to 999,” she says.

“So 100 digits of pi is just a short contemporary dance story of around 35 movements. It’s just scaffolding new information on to things already easy for me to remember.”

Woolmer is now training to beat the Australian record for pi figure recall (10,533 digits). “I could beat that in a week of learning,”she confidently says.

‘A surgeon couldn’t Google every answer’

Other than a glorious geek-out, how useful is this skill?

Woolmer works full time in finance. “It sounds ridiculous but I don’t have to reopen tabs on my screen to recall data and figures I need,” she says. Having fewer tabs open may seem like a trivial feat, but Woolmer pushes back on this.

“A surgeon couldn’t Google every answer they need when in the operating room,” she says.

For actors in verbose plays, or politicians like Bill Clinton able to charm voters by remembering hundreds of names, it’s certainly still a valued professional trait that quick research on the internet cannot disrupt.

Huggan finds his superlative memory an enormous aid to his sales job and not just at Christmas party time. “I’ll say to a potential client – I remember all of them – ‘You had a $60k budget and you wanted to sponsor an event’.” It helps with presentations too. “You’re able to do the sales pitch there and then rather than return to your notes.”.

‘It can absolutely get lonely’

While many of us might relish better memories, it can be a case of being careful what you wish for. If you’re the only one in your group who remembers an anecdote or detail, it can be potentially maddening.

“It can absolutely get lonely,” Robinson says of Hsams. “Becky [Sharrock] was in last Friday, and saying how she’s having to learn for it not to disrupt her life. It’s a compulsion – she can’t switch the memories off. It’s an affliction, in a sense.”

Glowacki relates to this. “Some events I’ve seen or heard I’d just like to forget, but I can’t,” she says. “When bad things happen to me, when I had arguments that escalated or when I misbehaved.”

She tells me she feels special when she gets tested on her memory. So we finish on a calendar date, selected by me at random: 1 September 2003.

“Monday,” she says. “We watched Finding Nemo at the cinema. I wore a maroon tracksuit and pale blue shirt underneath. I cried because I saw a pink sticker I wanted.”

She waves goodbye on Zoom, then I Google the Australian release date of Finding Nemo: 28 August 2003 – 13 years before the sequel, Finding Dory, gently mocked something Glowacki sometimes yearns for: the ability to forget.